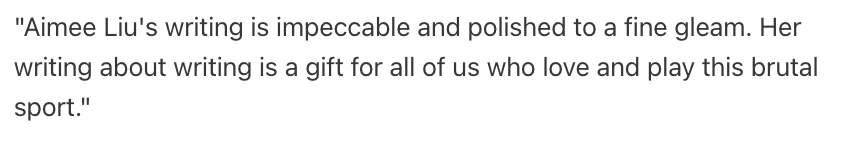

Le Garcon Magnifique

Glorious Boy in French translation,

published by Mercure de France!

Glorious Boy is also available as an audiobook!

"The most memorable and original novel I've read in ages… evokes every side in a multi-cultural conversation with sympathy and rare understanding."

– Pico Iyer, author of Autumn Light

Finalist for the 2020 Staunch Book Prize

BOOKLIST'S TOP 10 HISTORICAL FICTION OF 2020

Good Housekeeping's "Best Books of 2020"

Brit+Co's 12 Books That Will Take You on a Literary Vacation

A tale of war and devotion, longing and loss, and the power of love to prevail…

“Reminiscent of the tone and atmosphere of Somerset Maugham and George Orwell’s Asia-set novels, Glorious Boy is a Second World War story of adventure and loss, uniquely set in the Andaman Islands, one of India’s farthest flung territories” – Asian Review of Books

"In 1942, Claire Durant waits with her husband and young son for the all-clear to leave the Andaman Islands, where they’ve been stationed since 1936. The Andamans, east of India in the Bay of Bengal, are home to a colony of Burmese and Indian convicts as well as the native people, the Biya. Claire, a budding anthropologist, has been studying the Biya and getting to know them, but as WWII intensifies, she has no choice but to leave the people she loves. There is one other complication: Naila, their young servant, has a special relationship with Claire’s son, Ty. And when Naila disappears with Ty, there’s no telling what will happen to the family as they are wrenched apart. This fascinating novel examines the many dimensions of war, from the tragedy of loss to the unexpected relationships formed during conflict. The Andamans are a lush and unusual setting, a sacred home to all kinds of cultures and people, and Liu’s prose is masterful. A good choice for book groups and for readers who are unafraid to be swept away." --Booklist STARRED review

Subscribe to Aimee's newsletter HERE

To read an Excerpt from Glorious Boy

OF THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS

Read Aimee's essay on the origins of Glorious Boy in LitHub --HERE

Latest Blog posts:

MFA Lore: Your Essential Writing Resource

.png)

The blog posts here represent a small sample from my Substack publication, MFA Lore, where I share the wealth of insight that I’ve gleaned over more than four decades of publishing and teaching creative writing at the MFA level.

Why MFA Lore? I know there’s some dispute about the value of graduate degrees for writers who “just want to write.” I shared that hesitation for years, publishing more than three novels and four nonfiction books before getting my own MFA at Bennington. But the knowledge and community I gained at Bennington, followed by 15 years of teaching MFA students at Goddard College, ignited my writing life and improved my work in too many ways to count. My goal here is not to motivate you to get an MFA (unless you’re so inclined, of course) but to give you the essences of an MFA education--mius the tuition!

To Make Your Writing More Memorable...

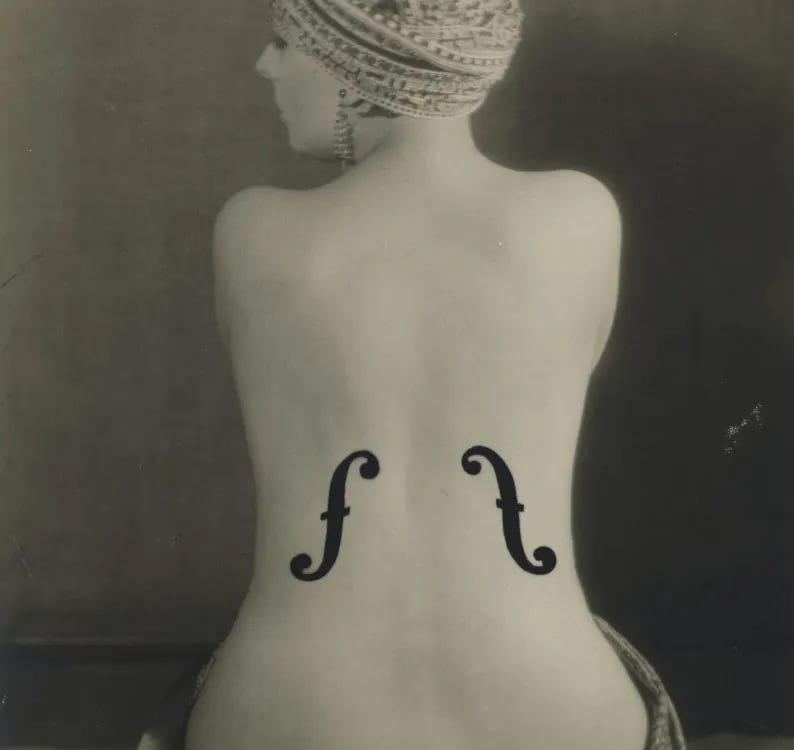

I tripped across a fascinating study the other day that offered an essential nugget of scientific insight for writers, and I want to share it with you here.

Yale researchers have been studying the “stickiness” of memory:

The human brain filters through a flood of experiences to create specific memories. Why do some of the experiences in this deluge of sensory information become “memorable,” while most are discarded by the brain?

They used a computational model and behavioral study using visual imagery to answer this question. Subjects were shown a rapid series of pictures, then asked to recall them. It turns out, the most memorable scenes were the ones that didn’t immediately make sense.

For example, a picture of a bright red fire hydrant deep in the woods would be easier to remember than an image of a bunch of deer bounding through the same forest. A mountain with a clown standing on the summit is more memorable than a peak with a climber planting a flag. A beach studded with giraffes is mentally stickier than a beach littered with starfish.

“The mind prioritizes remembering things that it is not able to explain very well,” said Ilker Yildirim, an assistant professor of psychology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and senior author of the paper. “If a scene is predictable, and not surprising, it might be ignored.””

This got me thinking about the many ways this rule applies to art— and how we can use it to make our writing more memorable. So that’s what I decided to explore in this week’s post.

Read the full post in MFA Lore on Substack by subscribing HERE

The 3 M's That Forecast a Bestseller

.jpg)

Hi Everyone,

This past week I had the privilege of chatting with several senior editors and publishers from major houses in NY. All were interested in the new book I’m ghosting and, while I can’t tell you anything about our specific project, I did pick up an editorial formula that might interest you. It’s how one publisher predicts which books will be bestsellers.

Subscribe and read the full article HERE!

Power Up Your Passive Protagonists!

Hello everybody,

Here's the latest from my MFA Lore newsletter on Substack

I’m back in the MFA archives again, mining gems that could bring value to your writing life. Today’s diamond in the rough is a letter about passive protagonists that I wrote to one of my most talented MFA advisees. With her permission, I’m going to share pertinent sections of this letter with you because, over the years, I’ve found that many, if not most of us, unwittingly hobble our protagonists in the inception. Activating them, then, becomes a priority in revision.

This advice is geared primarily toward fiction writers, but I urge memoirists to take note, too. When we write our own stories, we need to cast ourselves as active narrators, plunging into the past to rescue buried truths. There’s nothing passive about that role, yet it can be difficult to see and write ourselves onto the page in a truly active voice.

Passive protagonists and narrators are especially common in the work of female writers born into generations that discouraged or prevented women from speaking up, acting on their desires, and fighting for their rights. Women who were raised to hold themselves back, to mind their tongue, suppress their desires, and behave like “ladies,” could be forgiven if they struggled to speak their minds and demand the attention they deserved. For more than a century, then, the muted struggle between expression and restraint supplied the dramatic tension at the heart of fiction like Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Sylvia Plath’s The Belljar, and Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. But interest in such straitjacketed characters has waned in the era of Olive Kitteridge, Lisbeth Salander, and Hermione Granger. And that’s a problem for writers like me.

Visit MFA Lore @Substack to read the whole articleIntricacies of POV

This is the biweekly writers’ Q&A from the MFA Lore section of Aimee Liu's Legacy & Lore newsletter @Substack.

Become a paid subscriber HERE to read the whole Roundup.

Welcome to our second Roundup, everyone!

I appreciate this week’s terrific questions. I’m in the thick of these same issues with my own work, so it was good to give them a bigger think here.

Before we plunge in, please remember that writing is a game that requires us to break as many rules as we observe. Prescriptions are for pharmaceuticals, not literature. So, while these answers reflect my literary preferences and experience as an author and teacher, they’re only my advice. Never forget that you are the author of your work, so the ultimate decision for what goes on in your pages lies with you.